With a market cap of $147B, USDT (USD Tether) is now the world’s largest stablecoin. In 2019, it had a market cap of around $2B. Tether has been growing rapidly. Is this a problem for global financial stability? A couple of years back I published a piece in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review alerting policymakers to possible storm clouds on the horizon; see here. Rest assured, dear reader, I’m not an alarmist. But I do believe policymakers need to be prepared for all important contingencies, even if they appear remote at the time. The remoteness I alluded to a few years ago, however, is now vanishing rapidly.

Let’s start with some basics. A stablecoin is a fixed exchange rate system. There are many types of fixed exchange rate systems. They all share the same basic principle. The US government fixes the exchange rate between Lincoln paper bills and Washington paper bills at 5:1. The US commercial banking system fixes the exchange rate between commercial bank deposits and US government currency at 1:1. Government money market funds (MMFs) fix the exchange rate between their shares and government money at 1:1. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority fixes the exchange rate between the HKD and the USD at 7.8:1. Tether fixes the exchange rate between USDT and the USD at 1:1.

Fixed exchange rate systems are useful because they help facilitate payments. By construction, they eliminate the capital gains and losses associated with nonmonetary financial instruments. At least, this is the intent. But it doesn’t always work out the way it is intended. Our history books are full of accounts of banks subject to “runs,” of money funds “breaking the buck,” and of currency boards subject to “speculative attacks.” Will future money and banking classes include the “untetherings” of stablecoins?1

“Bank fragility” arises when one party (e.g., Tether) decides unilaterally to issue liabilities redeemable on demand at a fixed rate of exchange for the liabilities of another party (e.g., the US government). This would not be a problem if the first party designed its balance sheet to be perfectly safe (i.e., able to honor any redemption request with no difficulty). Unfortunately, a perfectly safe balance sheet is less profitable than a risky balance sheet. Assets subject to credit and liquidity risk produce more expected income than physical cash. Liabilities that offer state-contingent returns (e.g., equity) are a more costly form of finance. The US commercial banking system has largely solved this problem through regulation and government support. Money funds do not have the benefit of FDIC insurance or the Fed’s discount window, but they are restricted to hold short term government debt, which is relatively safe and liquid. An entity like Tether, however, is more like an unregulated (and uninsured) shadow bank. Is Tether set up for an untethering?

Let’s take a look at what Tether says on its website here. The home page provides the following reassuring message:

Transparency is sold as a big feature of DeFi. It is interesting to note, however, that the canonical model of bank runs (Diamond and Dybvig, 1983) features perfectly transparent bank balance sheets. So, whatever the merits of transparency, it will not (on its own) guarantee run-proof banking; at least, not in theory.

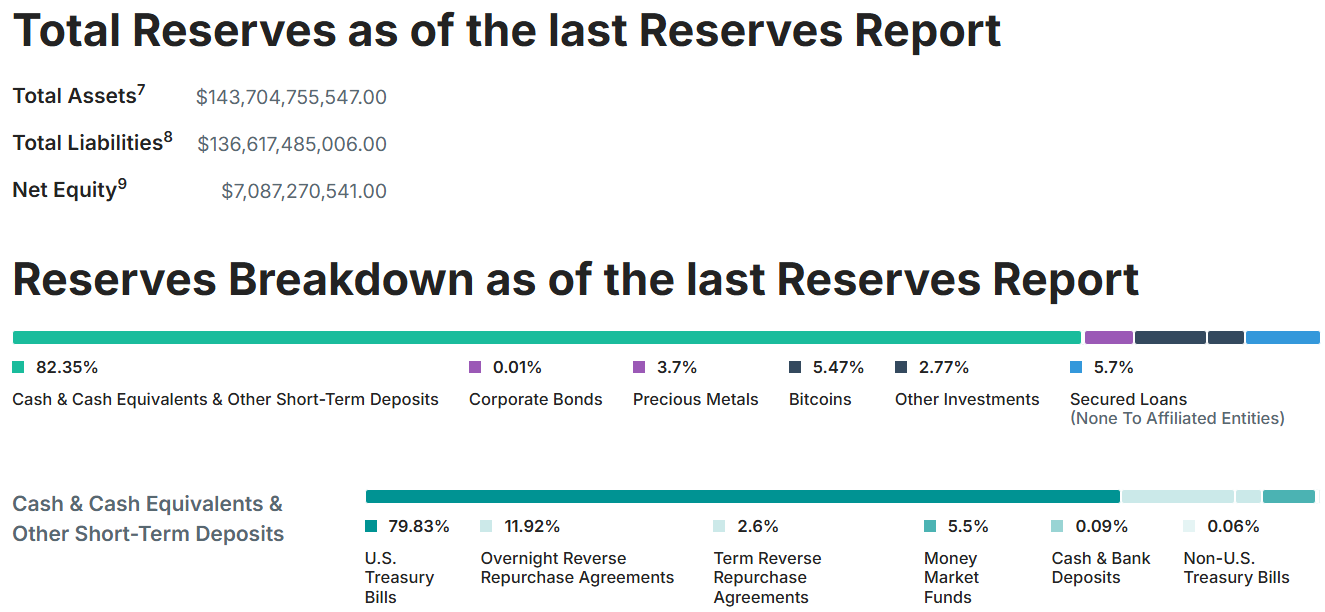

The second thing to note in the message above is the assurance that USDT tokens (i.e., bank deposits) are backed 100% by Tether’s Reserves. “Reserves” is one of those words that can have many different meanings. We know that (given the sums involved), “reserves” does not mean USD currency. Nor can “reserves” mean Federal Reserve account balances (Tether does not have a Fed Master Account). So what are these “reserves” if they’re not USD bills or reserves at the Fed? To its credit, Tether provides us with the needed information:

Tether’s (raw) capital ratio is about 4.9% (7/143). While this is in the neighborhood of US banks, it is far off the capital ratios observed in less-regulated “free banking” eras. But we can’t evaluate this number without looking at the asset side of the balance sheet. Here, we see roughly 80% in “cash” and 20% in a riskier set of assets. A 25% drop in the value of these riskier assets would wipe out Tether’s capital buffer. Improbable, perhaps — but not impossible. In any case, depositors can rest easily knowing that 80% of Tether’s assets are invested in “cash.”

Wait a second though. It appears that 20% of that “cash” consists of repo and deposits at money market funds. While these investments likely have little credit risk, they are still subject to counterparty risk. The same is true of Tether’s holdings of US Treasury Bills. Since Tether is not a US person, it cannot hold US Treasury securities directly at (say) Treasury Direct. Instead, Tether owns its US Treasury bills through Cantor Fitzgerald, a financial services firm recently headed by the present US Secretary of Commerce, Howard Lutnick. There are different levels of risk here. First, we know that there are times when the liquidity of even US Treasury securities is sometimes tested. Second, there is the counterparty risk associated with Cantor Fitzgerald itself.

So the question is, what happens if there’s an event that triggers a run on Tether? Experience suggests that a run event may be triggered by a significant loss of capital (say, because risk assets underperform) exacerbated by a (possibly) self-fulfilling prophesy whereby nervous depositors force Tether to dispose of its assets at large volume in stressed (thin) markets. If Tether’s counterparties have to unload a large quantity of suddenly illiquid securities to raise the cash for Tether to honor its peg, will it be able to do so in an orderly manner? Would the Fed lend a hand to help stabilize money markets?2 This is the conundrum that US policymakers face. If Tether was sufficiently small, then letting it fail would not pose much of a problem—the spillover effects would be minimal. And while Tether is still relatively small, it continues to grow rapidly. It is not a stretch to imagine Tether one day being the preferred way for multinational firms to make payments throughout the global supply chain. If and when that happens, Tether will become too big to fail. Indeed, TBTF status may be exactly what Tether and its depositors are seeking.

How should policymakers respond to this possibility. Direct regulation of Tether is impossible, unless Tether willingly submits to it. Regulation of Tether’s counterparties (like Cantor Fitzgerald) to guard against Tether’s growing systemic risk is possible, in principal. Another approach is for the US Federal Reserve to issue a competing product. Is it time for a Fedcoin?

I limit my discussion of stablecoins to those that back their liabilities primarily with non-crypto assets. This rules out objects like MakerDAO and Terra Luna (which did fail).

Note that Tether already did briefly break the buck in the spring of 2022. My reading of events is that Tether managed that crisis very well and has since trimmed back on its commercial paper holdings. In 2022, however, Tether was still relatively small (so that required asset sales were correspondingly small and not very disruptive). The question is how Tether would have managed a redemption flow one or two orders of magnitude larger?

"The Hong Kong Monetary Authority fixes the exchange rate between the HKD and the USD at 1:1" that is not the rate

I get the feeling that the whole purpose of the above analysis is to support the author's preference for seeing a Fedcoin, or CBDC, being proposed, like the Digital Euro the ECB is actively working on.

A Fedcoin is an extremely interesting topic in itself, that should receive a thorough, in-depth analysis of its merits and potential drawbacks.

I find the indirect approach chosen by the author "eyebrow raising"... The risks taken by Tether depositors are supposedly well known by those that chose to work with USDT, is there anything to point out that either:

1. They don't understand what they are doing, or that

2. Tether actively misleads them?

I find it a pity that more specific figures are not being brought to bear in this discussion. In the Terra Luna UST meltdown, USDT was worth about 80 Billion, not a lot less than today. It served about USD 10 Billion in redemption request in about a week, without forcing a haircut on depositors. The fact that the markets wobbled and some USDT holders panicked and sold at less that 1:1 can hardly be blamed on Tether IMO.